What was Baker’s artistic process?

Baker’s Initial Concepts

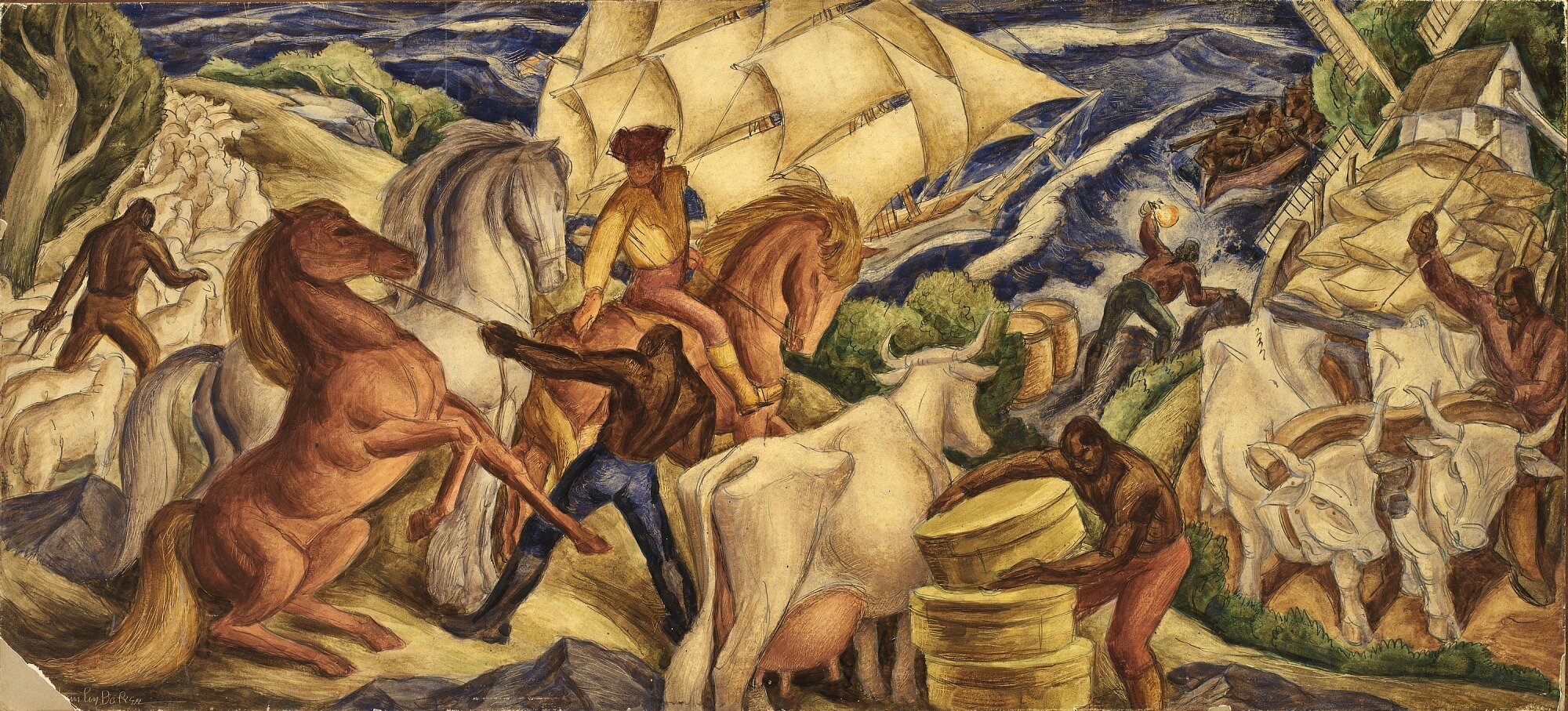

Baker spent nearly three years, off and on, developing and painting “Economic Activities in the Days of of the Narragansett Planters,” which he called one of the greatest works of his lifetime. The painting was a departure from Baker’s normal commercial work, and it required intensive research, interpretation, and development of representative imagery. The large scale and special painting techniques the mural required were particularly challenging for Baker, who was trained primarily as an illustrator. In fact, few New Deal mural artists had any experience in the medium.

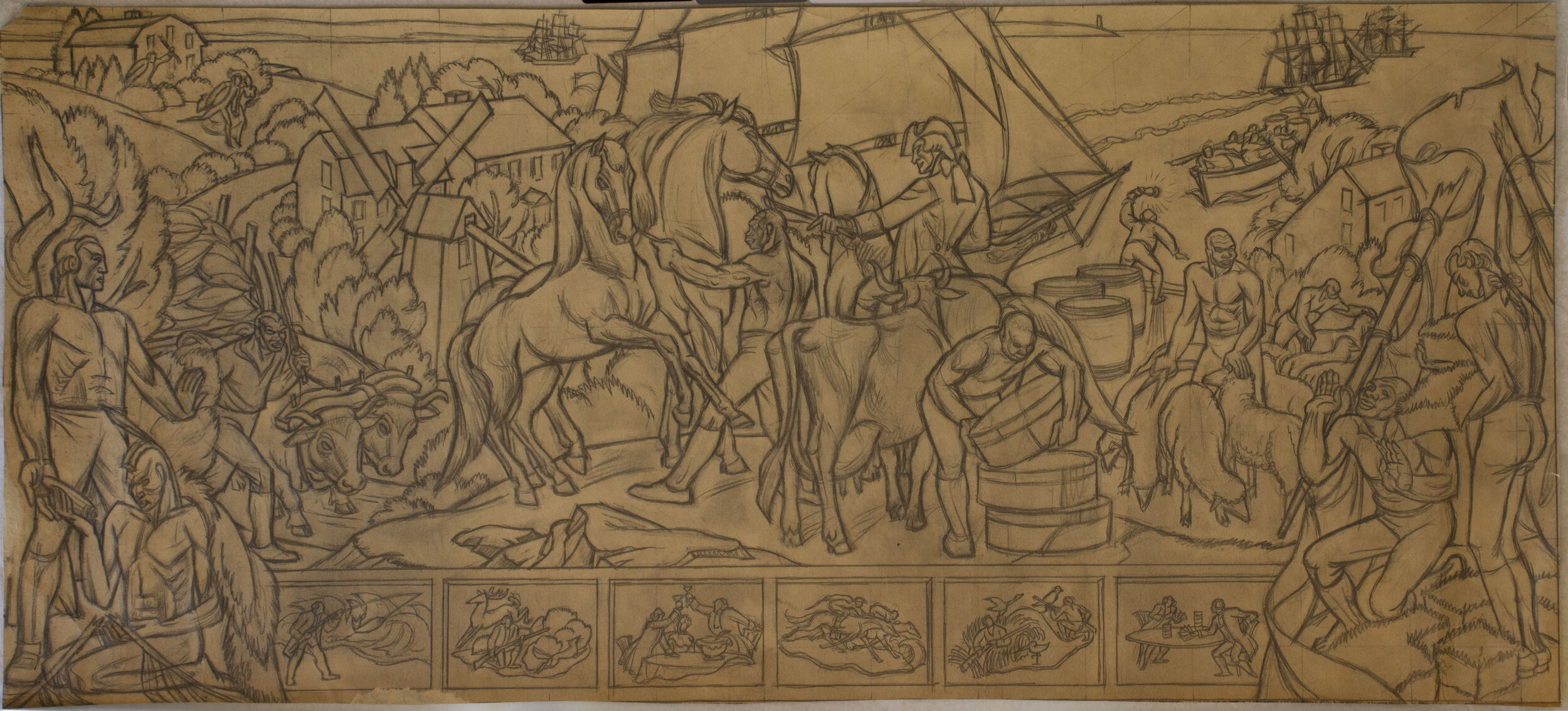

In his initial concepts, Baker depicted many aspects of mid-18th century life in southern Rhode Island. Along with the agricultural and trade activities depicted in the final version of the mural, Baker incorporated several more subjects into his initial sketches, including: Native American, Black, and European figures symbolizing the rise and decline of “Planter society;” Hannah Robinson and her lover; vignettes of hunting, fishing, horse-racing, gambling, and feasting; and a wind-powered mill and plantation house. In a later magazine article, Baker shared the motivation for his initial concepts, “I convinced myself that non-income-producing industries also should be shown, that their [the Planters] civilization’s rise and decline should be symbolized, their [the Planters] pleasures recorded, and space given to architectural and even romantic items.”

Exhibit Navigation

1: Introduction

2: Ernest Hamlin Baker

3: Great Depression & New Deal

4: Treasury Section of Fine Arts

5: Baker’s Commission & Research

6: Slavery in Southern Rhode Island

7: Baker’s Artistic Process

8: The Finished Mural

9: Wakefield Post Office

10: Why the Mural Matters

11. Share Your Thoughts

12. Further Reading

Baker Grapples with Difficult Artistic Choices

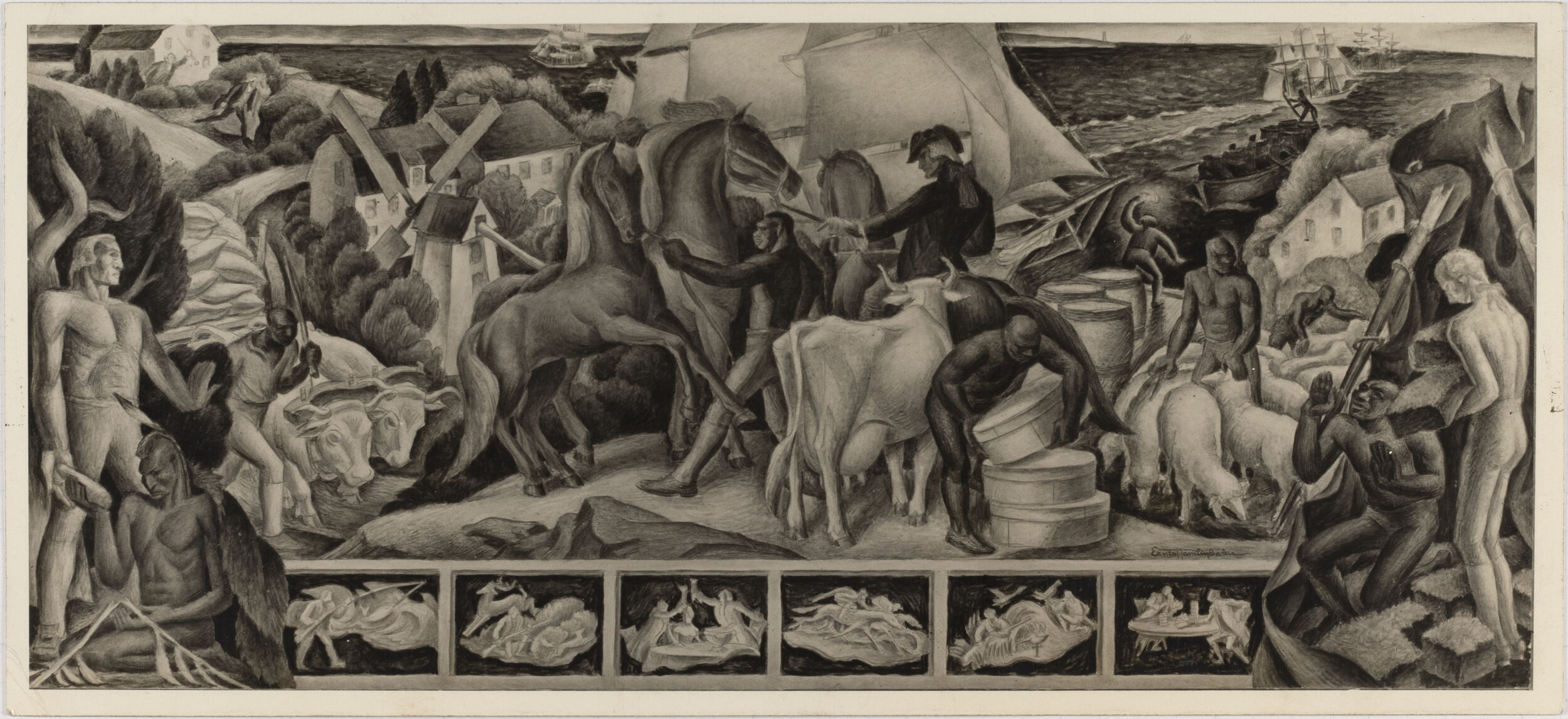

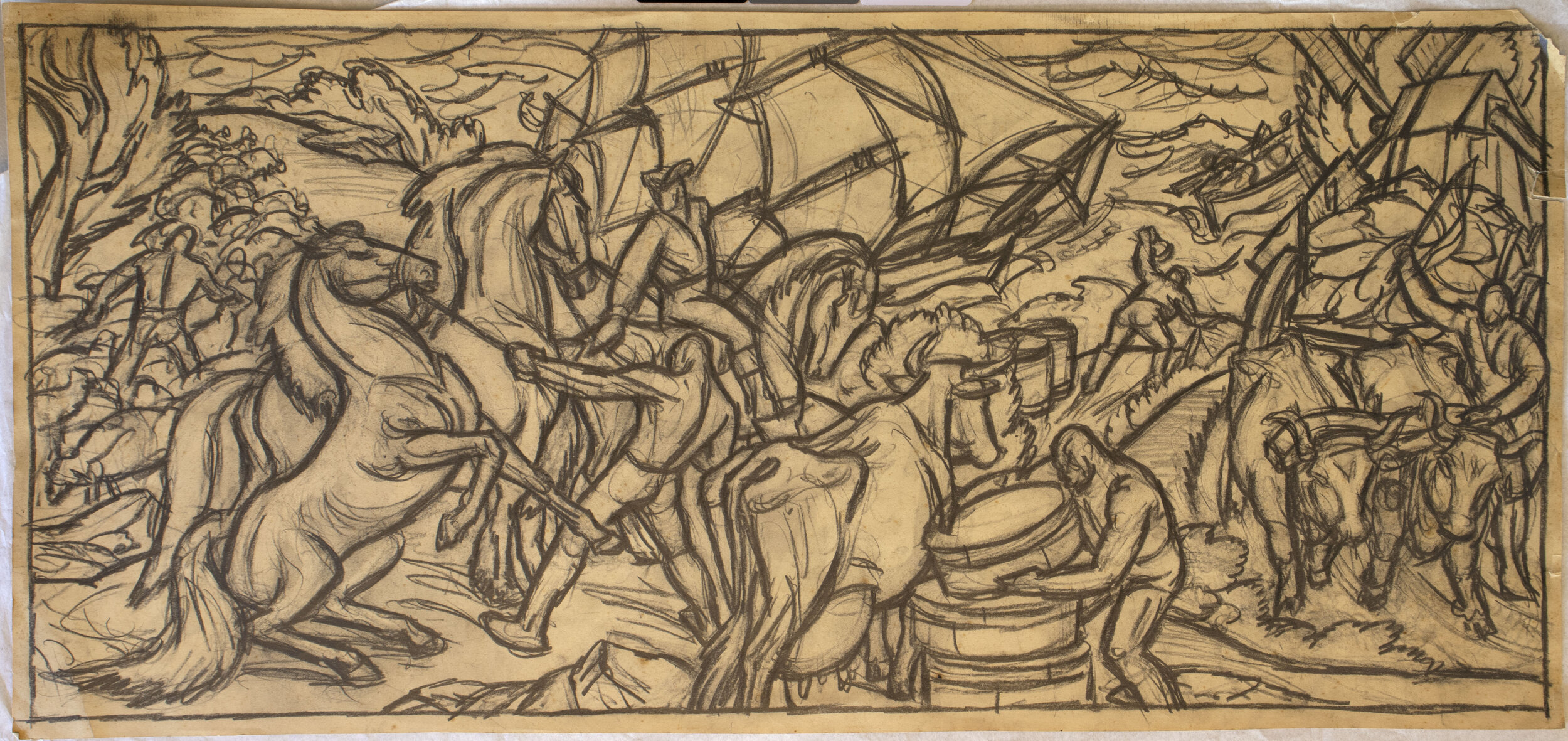

Baker received feedback on his initial sketch from his supervisor at the Section, Edward B. Rowan, who found the composition, the arrangement of visual elements, too crowded. The next version reflects adjustments made due to Rowan’s feedback, including the new placement of smaller vignettes of hunting and leisure activities to a series of small panels at the base of the painting, reducing the crowding of the central design. Although the Section approved this version of the mural composition, its complexity continued to vex Baker as he continued to develop the painting. So, after several months of working on his first idea, Baker radically reworked the drawing, narrowing his focus to the people and core activities that drove southern Rhode Island’s colonial economy.

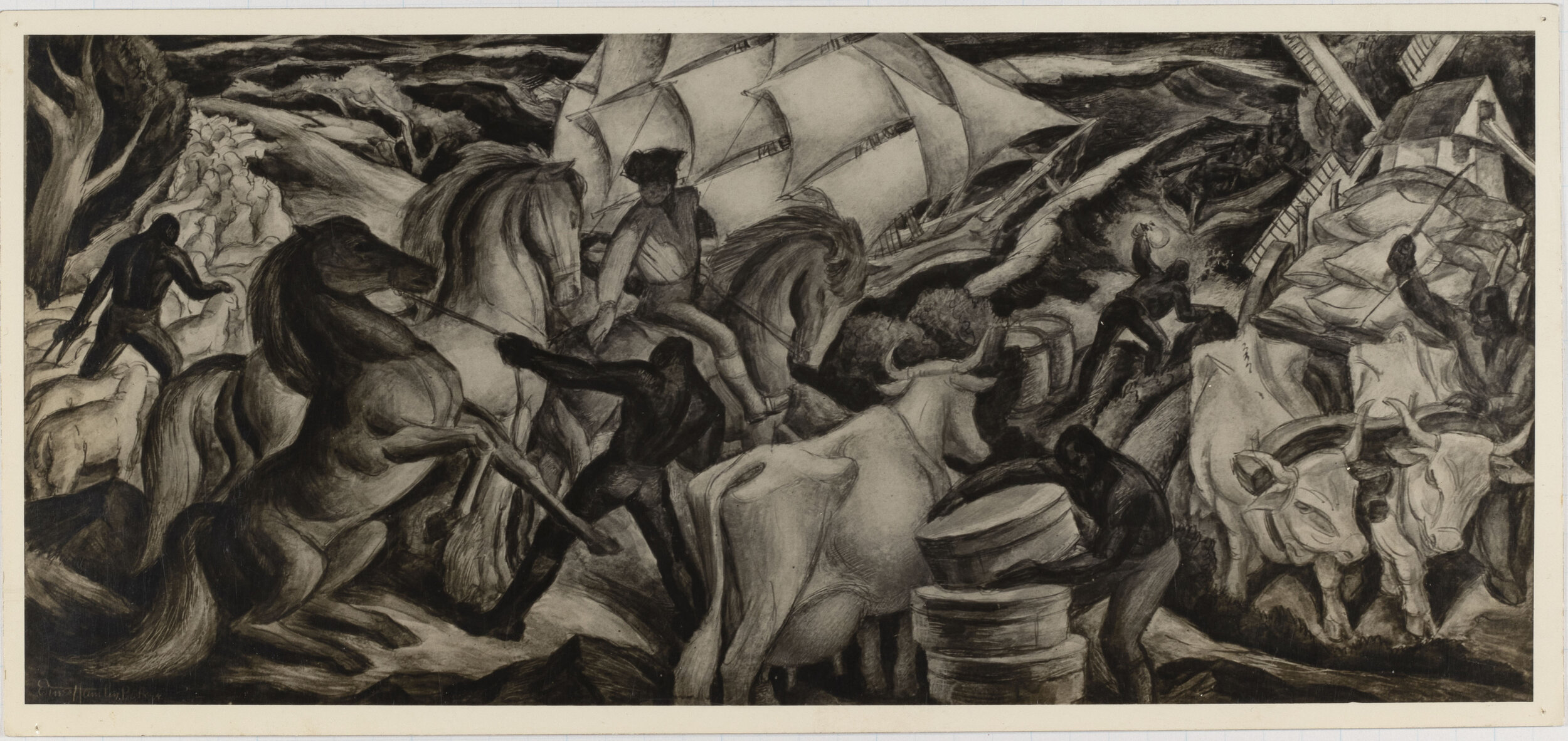

In this new version, Baker removed all symbolic figures and vignettes and instead focused on creating an interwoven scene depicting the activities that were the foundation of the colonial economy: stock and dairy farming, grain production, horse breeding, and rum smuggling. Baker distilled the human figures down to three symbolic labor roles: enslaved people engaged in agrarian labor, a Narragansett Planter dictating the labor, and smugglers running rum along the coast. After settling on this imagery, Baker worked on refining his design for several more months, until finally he began the painting process by making a detailed sketch of the scene onto the canvas.

A Complex Process: Baker’s Challenges in Painting the Mural

There were delays throughout this process of developing and painting the mural for a number of reasons: difficult artistic decisions, Baker’s extended illnesses, using a complicated painting technique, and other assignments to continue his income between receiving payments for the mural. One of these assignments, completed in 1939, actually marked the start of the next major phase of Baker’s career and his defining work as an artist: illustrating portrait covers for Time magazine.

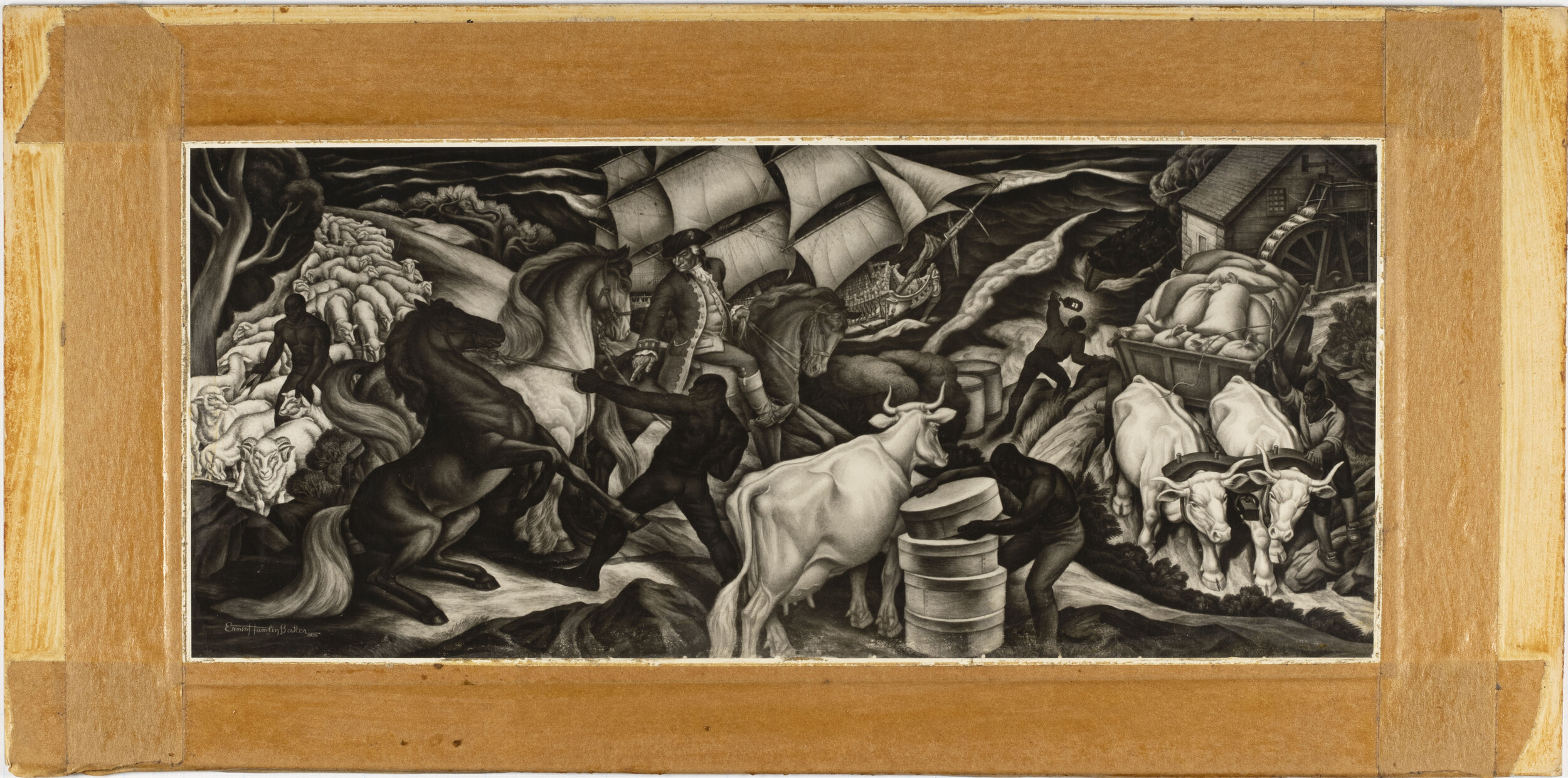

Much of the delays, though, came from the oil painting technique Baker used, in which he gradually layered transparent oil paint over the detailed base sketch. Baker attributed these difficulties to the fact that he had never worked with the oil painting method in such a large format. Even small changes in one part of the mural would require him to make time-consuming adjustments throughout the whole piece. While challenging, this method of oil painting made it possible to infuse Baker’s personal style throughout the mural. The painstaking process caused Baker to work long hours in the final stage of the mural, and throughout the project, Baker and his supervisor Rowan exchange letters about the progress of the mural. Although Baker was continuously behind schedule, the work he delivered to the Section was always met with praise for its excellent quality.

Baker’s mural in progress. At this stage, Baker had prepared the canvas with a white lead ground and was in the process of filling in a detailed sketch that would underlay the layered transparent oil painting. This technique gives the painting its sharply defined, detailed style, which became Baker’s signature for the rest of his career. baker collection, south county history center.

Baker Finishes the Mural

When Baker finally finished and installed the mural at the Wakefield post office in December 1939, two years after its expected completion date, local news coverage praised the exceptional quality of the painting. Articles also pointed out that the mural plainly depicts some aspects of southern Rhode Island’s colonial history that some residents may not want to acknowledge. Baker was happy to receive any publicity he could get for the mural: he showed reproductions in galleries in New York, at least two magazines printed reproductions, and he wrote a six-page article about his development of the mural in Art Instruction magazine. Baker continued to use the layered oil painting style in his work for Time, an iconic style of the magazine’s covers for the next two decades.

Banner Image: Baker’s mural as published in LIFE Magazine, January 27, 1941

This exhibit is made possible through major funding support from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. The Council seeds, supports, and strengthens public history, cultural heritage, civic education, and community engagement by and for all Rhode Islanders.