What was the Treasury Section of Fine Arts?

“The Section”

The Treasury Section of Fine Arts (commonly referred to as the “Section”) was established by Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., in 1934 and operated until 1943. It was one of a few New Deal-era programs that lasted well into World War II. Lawyer, businessman, and painter Edward Bruce was appointed to director of the Section, a position he served in for the duration of its existence. Its stated purpose was “to secure for the Government the best art which this country is capable of producing, with merit as the only test.”

Most New Deal arts programs were established as work relief for unemployed artists, providing “home relief,” for persons experiencing unemployment and financial hardship. The Section functioned slightly differently: instead of artists applying for relief, Section artwork was commissioned through an anonymous, competitive application process. This meant that the Section could ostensibly employ both highly reputable artists and relatively unknown talents, based solely on the merits of their work. When an artist of exceptional talent applied, selection committees were allowed to forgo the competitive process, which is how Ernest Hamlin Baker won his mural commission in 1936.

Exhibit Navigation

1: Introduction

2: Ernest Hamlin Baker

3: Great Depression & New Deal

4: Treasury Section of Fine Arts

5: Baker’s Commission & Research

6: Slavery in Southern Rhode Island

7: Baker’s Artistic Process

8: The Finished Mural

9: Wakefield Post Office

10: Why the Mural Matters

11. Share Your Thoughts

12. Further Reading

from left, Edward Bruce, Director of the section of fine arts, First lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Asst. Treasury Secretary L. W. Robert, Jr., and Public works of art Project director Forbes Watson discussing plans for arts projects, 1934. Harris & Ewing Collection, library of congress.

“Democratizing” Art: Commissioning Public Art for Small Towns

Bruce and his program directors wanted to do more than just find high quality art to decorate federal buildings; their ambition was to “democratize” art by showcasing it in federal buildings across the country to give greater access to the general public, making fine art part of daily life. The Section’s leaders also hoped to expand the budding American Muralist movement, which was inspired by a similar movement in Mexico in the 1920s that included artists like noted artist and lifelong Marxist Diego Rivera.

When commissioning artworks, the Section’s direction to artists was to reflect the place where the artwork would be displayed, and often the Section tried to hire artists with a connection to that place. If the artist was not familiar with the location, they were strongly encouraged to visit the community and discuss possible subject matters of the painting with leading citizens. Overall, the pieces were meant to be honest, accessible, and to optimistically describe the people, activities, landscapes, and histories they depicted. (Many artworks did not meet that last criteria.) Artists typically developed several ideas for a mural’s subject, then met in Washington, D.C., or at a regional office with a supervisory board, which would select one of the themes to be the subject of the work.

The Styles and Themes of New Deal Art

Once the subject was selected, the Section allowed the artist to depict the subject as they wished, stylistically speaking, but their general guidance was that the subject of the mural should reflect the place and community where it would be displayed, and in a way that everyday people could understand. The styles favored by the Section were American Scene Painting, Regionalist, or Art Deco styles; it explicitly declined abstract and Avant-garde design submissions. Though the Section preferred to avoid politicized subjects, they ultimately allowed artists to portray controversial aspects or turbulent periods of American history. New Deal era murals continue to spark controversy and debate over the subjects they depict and how they depict them today.

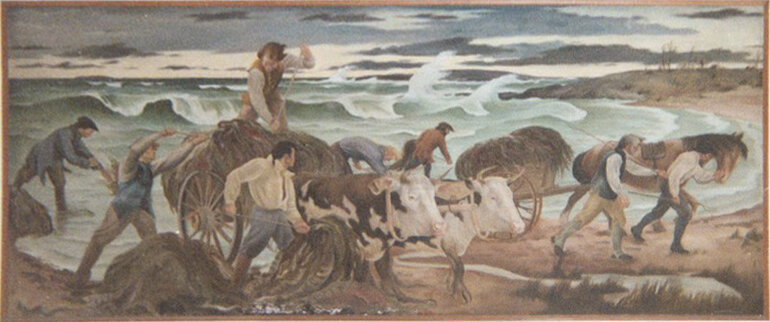

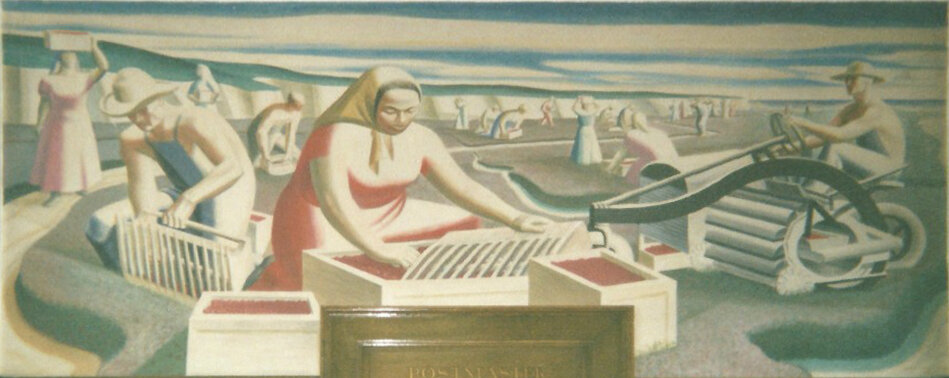

While historical events are a common theme of murals commissioned by the Section, a recurring aspect in much of the artwork is the depiction of labor. There was a good reason for this: the Great Depression was a dark time for all Americans, but industrial and agricultural workers were especially hard hit. Depicting the labor of everyday people, as well as the iconic industry of a place, was meant to inspire optimism and confidence in the American political and economic system. A number of labor-focused murals survive today in New England, including: Apponaug Fishermen in Apponaug, RI, Gathering Seaweed from the Sound in Madison, CT, and Cranberry Pickers in Wareham, MA.

The Section’s Legacy

In all, the Section commissioned $2.5 million (or $38 million today) in artwork: 1,116 murals and 301 sculptures that were placed in federal buildings (primarily post offices and courthouses) in cities and towns across the country. Although many works produced by federal arts programs during the New Deal have been lost, the Living New Deal project has located 1,276 works, about 90%, of Section-commissioned artworks.

Banner Image: Baker’s mural as published in LIFE Magazine, January 27, 1941

This exhibit is made possible through major funding support from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. The Council seeds, supports, and strengthens public history, cultural heritage, civic education, and community engagement by and for all Rhode Islanders.